Welcome to the third post of the series of the State of Art of Private Key Security for Blockchain Operations. This post will be entirely dedicated to the automatic signing of blockchain transactions, explaining some of the most common mistakes, and also mentioning all the different storage locations where private keys usually are (including the places where the keys shouldn't be!)

- [1/4]: Concepts, Types of Wallets and Signing Strategies

- [2/4]: Common Custody Solutions Architectures

- [3/4]: Private Key Storage and Signing Module (this post!)

- [4/4]: Approvals and Policies

One of the main questions that any project implementing its own private key management solution for hot wallets or operational keys needs to answer is: Where do we store the private keys? but before that, let's start talking about the only piece that should have access to these keys:

The Signing Module

One of the most common mistakes in centralized blockchain project architectures,is to not have a specific signing element. Even worse, spreading the private keys in clear text over multiple micro-services so all of them can sign operations. If one element is compromised (from an external or internal threat actor) then the private keys of the project will be compromised.

This is the element that has access to the private keys, meaning that it can use them for signing blockchain transactions. This does not necessarily mean the module has access to the plaintext private key, only that it can use it. How it accesses the private key depends entirely on the implementation and architecture. In some cases, private keys may be protected by hardware (e.g., in an HSM or KMS), and this module will have permission to use them. In others, this module may be implemented inside a secure enclave that decrypts the key securely within the enclave for use.

In most cases, this will be a service, running on its own, hardened environment, following the Principle of Least Privilege, and exposing a minimum attack surface. Even, to reduce and avoid exposing a server-side service, it can be developed to initiate the connection to another service (using mutual authentication).

As the module with access to the keys, it is one of the most critical components of any architecture involving blockchain operations. In a centralized custodial environment, this is considered a Single Point of Failure. Vulnerabilities in the design or implementation of this element may compromise the private keys. If this module is compromised, anything protected by the private key will be compromised.

The Signer module needs at least 2 "elements":

- The signer business logic: custom developed code that will receive a transaction and sign it with a private key

- Private Key Storage: A place to securely store the keys for its use

Signer Business Logic

The most basic case would be a service receives a transaction or message from a trusted source, and signs the operation with the private keys.

Depending on the implementation, this signer may just have a connection with an HSM or Cloud KMS and request to sign a transaction, or may be able to obtain the private key to sign the transaction.

One of the most important aspects to consider to the logic, is to be able to properly authenticate the signing request.

If for example, the solution requires a prior off-chain approval by different participants or policies (we will talk about this in detail in the next post) then, having the signer to ensure that the transaction has been properly approved can protect an arbitrary, unapproved transaction that reaches to this service to be signed. This could be done by authenticating a request coming from the Approval module, or having it cryptographically signed by the Approval module.

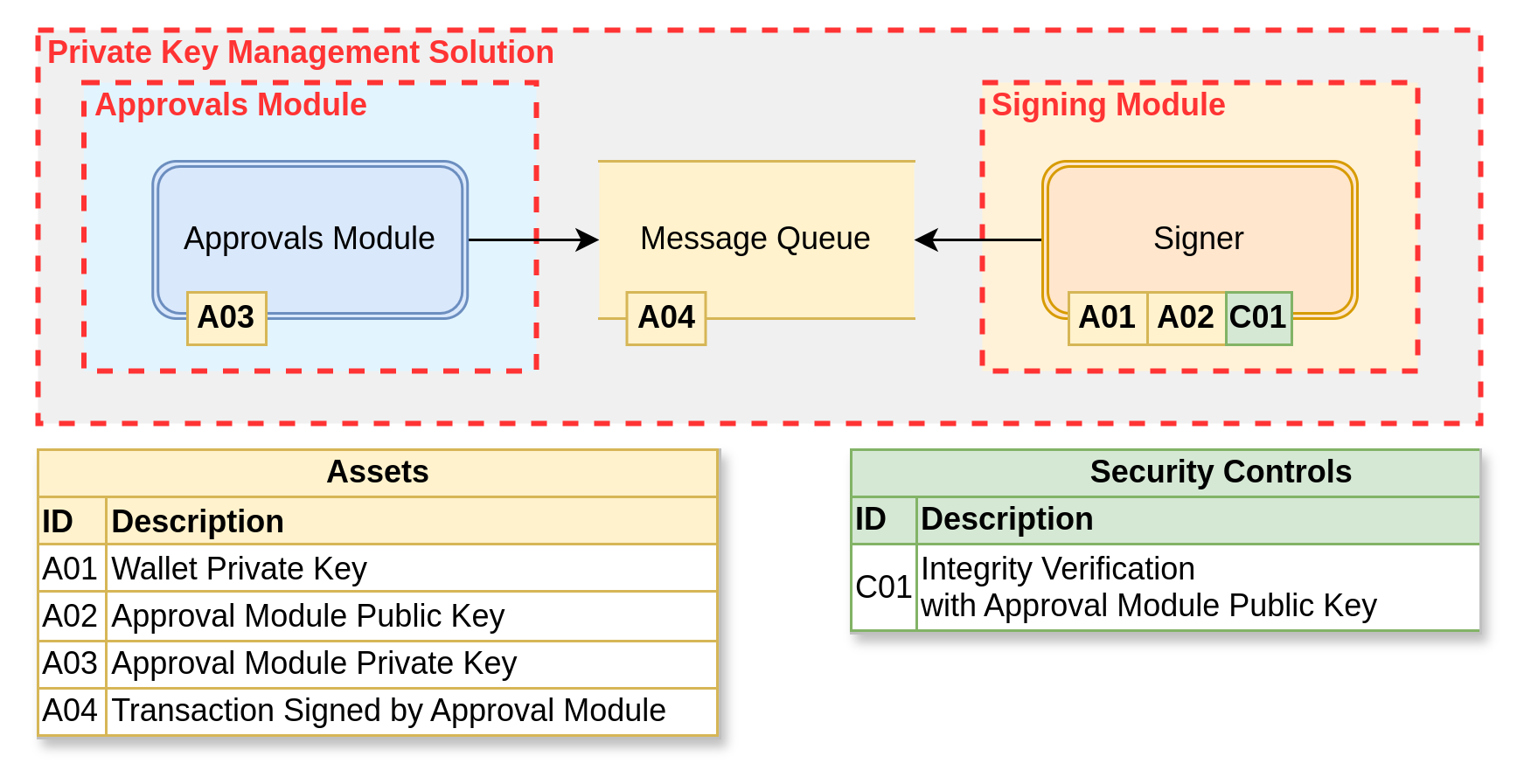

In the example below, the Approval module puts a transaction to be signed in a message queue, and the signer retrieves it from the queue, validating that it has been signed by the approvals module before signing the operation.

⚠️WarningWhat if someone is able to inject a message to sign in the message queue? That could bypass the approvals if there isn't a cryptographically signed operation!

Types of Storage for Operational Keys

Now that we defined the Signing module, let's explore some of the most secure storage methods for private keys, all hardware-backed, and how they can be accessed by the Signing module.

📝NoteThe examples below are simplified to highlight the main architectural patterns.

In practice, most custodial solutions combine several of these methods to achieve not only confidentiality of the private keys but also integrity of all operations, like using a cloud KMS connected to an enclave, or a hybrid model with both HSMs, enclaves and MPC signing.

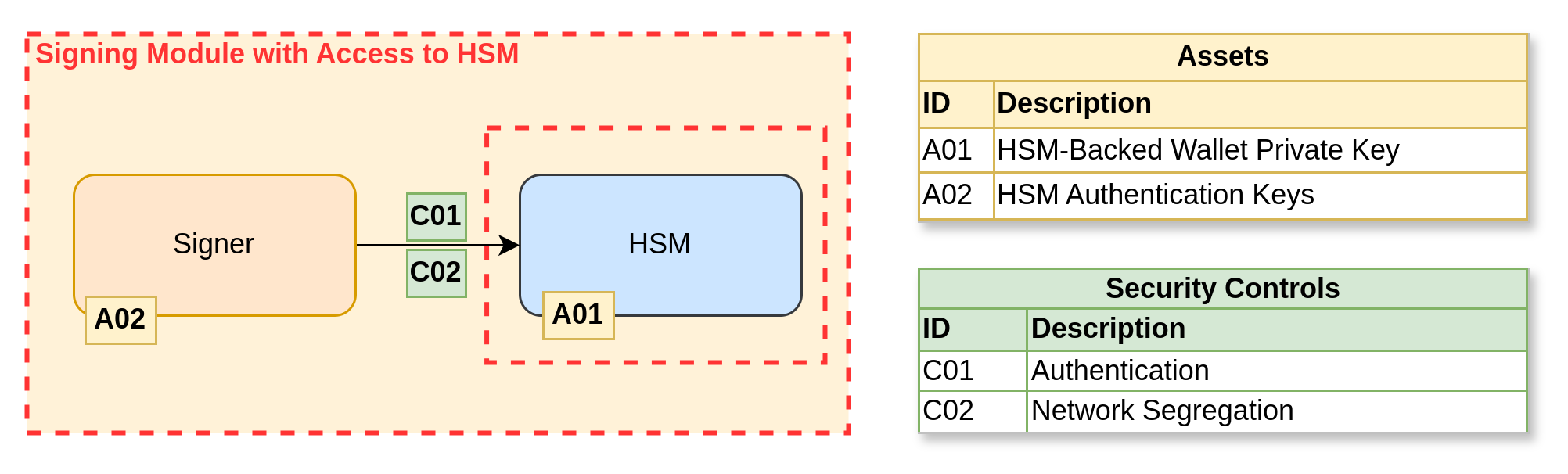

Hardware Security Modules (HSMs)

These are dedicated, tamper-resistant devices that can be configured so keys cannot leave the device, only sign requests.

The most important aspect of configuring HSMs is ensuring that no options allow private key extraction. A private key should never be extractable and should be generated inside the HSM. HSMs support different types of backup operations for restoration.

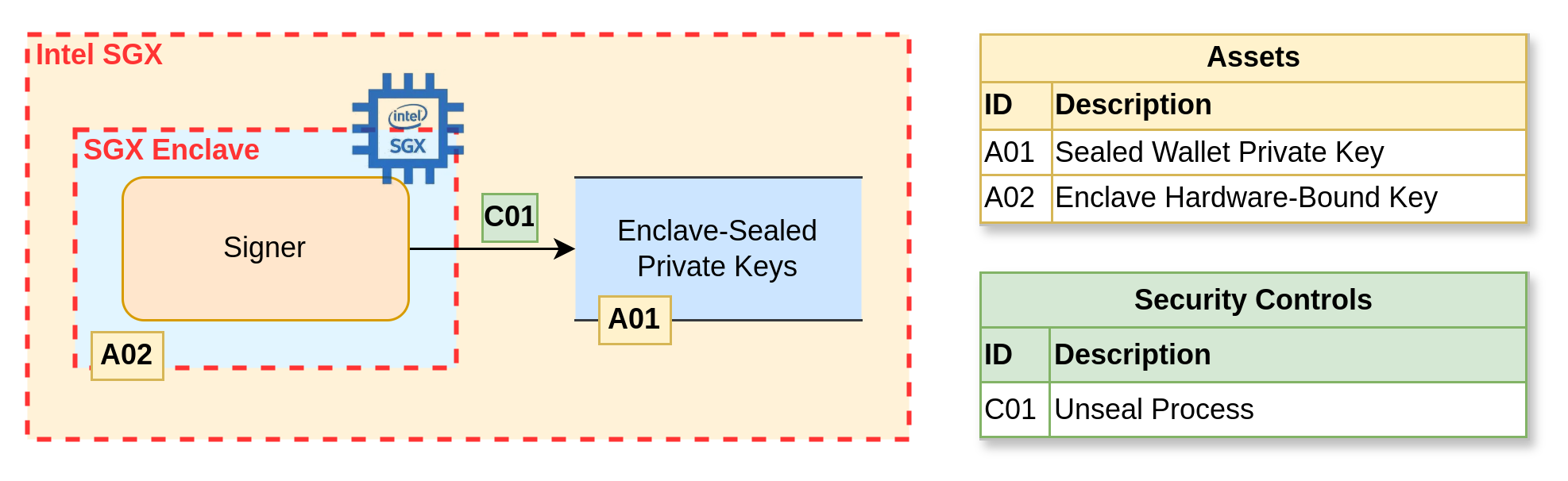

Secure Enclaves

Secure enclaves are isolated hardware environments that are often used for key operations without exposing the private keys. Some common examples we see often include Intel SGX, or cloud alternatives such as AWS Nitro Enclaves. The example below shows how a Signing service could look inside an SGX enclave:

However, an important risk to keep in mind with secure enclaves, something we were reminded of just a few days ago with the WireTap and Battering RAM vulnerabilities, is that we can't blindly trust them to protect our keys.

However, an important risk to keep in mind with secure enclaves, something we were reminded of just a few days ago with the WireTap and Battering RAM vulnerabilities, is that we can't blindly trust them to protect our keys.

What if a vulnerability allowed someone to extract the secrets from an enclave?

If that scenario would mean game over in your environment, it's a clear sign that additional mitigations are needed.

One effective approach is to require multiple, physically distributed enclaves (for example, using MPC) to jointly sign operations.

That way, even if one enclave is compromised, an attacker would still need access to several others, ideally in different, isolated locations, to fully compromise the system.

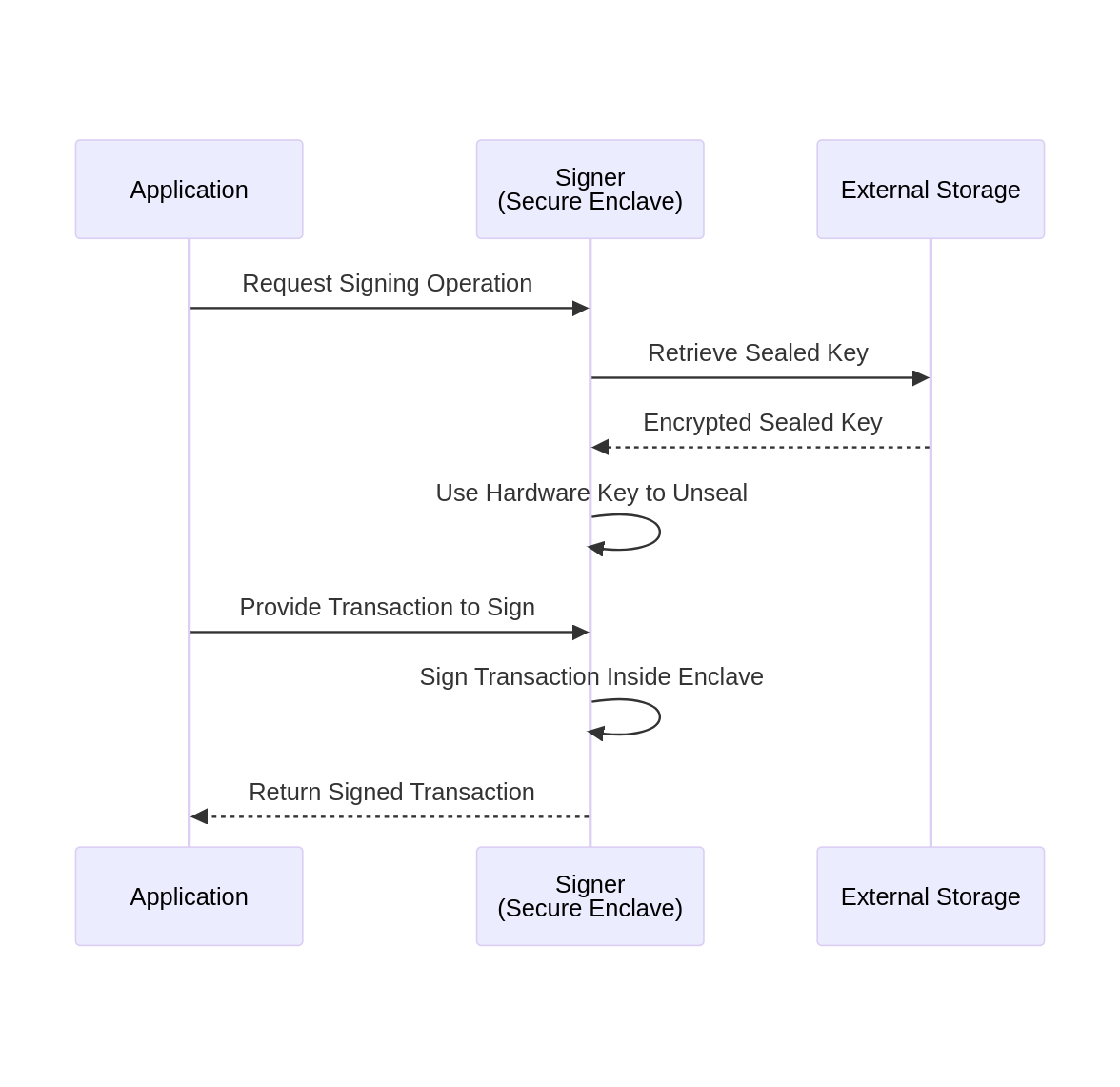

Secure enclaves do not have persistent storage, so any secret protected by the enclave must be securely stored elsewhere. Typically, the enclave generates the private key and seals it (securely encrypting it with a hardware key) before being stored externally, ensuring it can only be unsealed (decrypted) inside the enclave.

The diagram below illustrates (in a simplified way) a signer implemented in a secure enclave unsealing an externally stored key to sign a transaction:

Cloud Key Management Systems (KMS)

Cloud KMSs add a software layer that uses an HSM behind the scenes. While Cloud KMS solutions offer ease of integration, scalability, and managed security updates, they also introduce reliance on third-party providers and potential regulatory compliance concerns. Dedicated HSMs, on the other hand, provide greater control and isolation but require more effort in maintenance and security management.

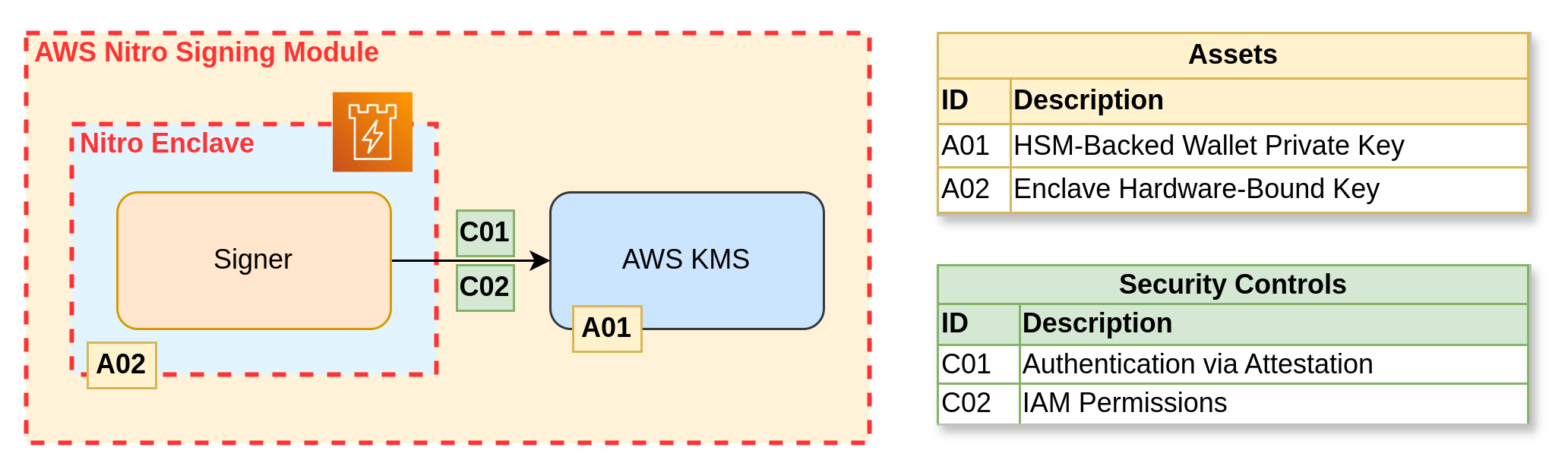

Sometimes, enclaves are used to execute the signer module while connected to an HSM or KMS. For example, in AWS Nitro Enclaves and AWS KMS, KMS supports cryptographic attestation for Nitro Enclaves, ensuring that a specific enclave with a specific configuration is executed for any KMS operation, such as decrypting or signing information. A signing module inside a Nitro Enclave could use AWS KMS to securely store the private keys:

Storage places that should be avoided

☠️DangerThe options below are not recommended for storing private keys, as are inherently more insecure than the options described above.

-

Software Based Storage:

- Secret Manager Services: Commonly used to store secrets like API keys, but they should not store private keys as they can be recovered.

- Encrypted Local Keystores: Private keys stored this way (e.g., Ethereum Keystore format) still require a passphrase. If the passphrase is weak, the keystore becomes vulnerable to brute-force attacks.

-

Other insecure places where private keys should not be stored:

- Environment variables: Often used when no secret managers are available, but any server compromise (or insider threat) would expose the keys.

- Configuration files: How many github projects ask you to write down a private key in a .env file?. Just modifying the github query from before to search more than the .env.sample files should be clear enough to understand why this is a bad idea. Storing private keys in clear text, and in a place that may end up easily uploaded to a repository is a recipe for disaster. Unfortunately it is very common to see open source projects requiring users to place private keys in this kind of files.

- Databases: If private keys are stored as plaintext in a database, a compromise (via SQL injection or insider access) could expose them.

- Hardcoded in Source Code: Developers sometimes store keys temporarily in the source code... until that is uploaded to a public Github repository by mistake.

Types of Storage for Private Keys in MPC and MultiSig Architectures

Apart from all the places we have just talked about, there are other common places where private keys related to the signature of a transaction may be stored. This is specially relevant for MPC and MultiSig wallets. Some centralized solutions also use additional private keys to protect the approval process when requiring manual intervention (a human approving the transaction)

- Hardware Wallets: Specialized devices like Ledger or Trezor. They are common for individuals or small teams for managing cold or warm wallets, and also common for solutions with MPC or MultiSig.

- Browser Wallets: They are more common for user initiated operations than in organizations for operational wallets, but there are many cases where these wallets could be involved. Two of the most common examples would be Metamask and Rabby Wallet. These software wallet, which allow users to directly interact in a Web3 application with a browser extension, also support to import a hardware wallet or connect to any custodial solutions via WalletConnect.

- Mobile Wallets: Modern devices running Android of iOS have secure chips that allow to generate private keys inside that cannot be exported from the device, protected by the Android KeyStore or the iOS KeyChain. The ability to protect these keys with biometrics and the usability of allowing a key in your always connected device in your pocket makes them a place that is used often to sign and approve transactions. For example, MPC providers such as Fireblocks allow their users to save their private key in the secure enclave of the mobile device with its application, from where they can approve (sign) the operations.

- Other software solutions. For automated operations or even operations without human intervention, the need for a number of signatures may require additional devices. For example, Fireblocks allows automatic transaction signing and approvals through their Co-Signer solution. A piece of software with one of the keys able to perform additional checks before signing a request.

We've looked at where keys live and how the Signer uses them, along with the pitfalls to avoid.

Next, we'll turn to the guardrails: Approvals and Policies, multi-party approvals, policy checks, and controls that decide what should be signed in the first place.